What leads a female convict to flee the fledgling Colony of NSW in the governor's cutter, and another to endure life at the ‘edge of legal occupation’?

In her novel titled Fled, author Meg Keneally creates the world of highway woman Mary Braund (nee Bryant, b. 1765 - ?), whom she believes was the mastermind behind the courageous escape by boat from the Colony of NSW on 17 March 1791. Through the character Jenny Trelawny, Keneally resists romanticising the experience of the female convict, and because there are no records written by Bryant herself, Keneally informs the extraordinary story with extensive research into first-hand accounts of the day through the journals of Captain William Bligh (b. 1754 - d. 1817), James Martin (b. 1760 - ?), and British marine officer Watkin Tench (b. 1758 - d. 1833).

Meg Keneally

We have been in dialogue with Meg regarding her novel - reflecting on the challenges of researching and describing the experience of female convicts, she has generously shared the following article.

Stranger than Fiction – the extraordinary truth behind Fled, by Meg Keneally

It’s an odd thing about historical fiction – the most outrageous, outlandish elements of a story are often the ones which are based on fact. Yet even the most extraordinary true stories have nothing on the true tale of convict Mary Bryant, the woman behind one of history’s greatest escapes.

Fled book cover Cover design by Alexandra Allden. Cover images: Nicole Wells / Joanna Czogala Arcangel Images (woman), Blend Images/Alamy Stock Photo (boat, sea).

Mary was sent to Australia with the First Fleet in 1788, part of a group of prisoners who England wanted to excise from the civic body. She masterminded a plan to steal governor’s cutter, a small open boat. She sailed it with her husband, children and seven other convicts from Sydney to West Timor, passing herself off as a shipwreck survivor before her luck ran out and her identity was revealed.

I first heard Mary’s story from my father, on long road trips in the days before iPads. I assumed he was making it up. Dead-of-night escapes? Sea chases? Survival against impossible odds? Surely such things didn’t happen. But when I returned to the story as an adult, I was amazed to find he’d actually been quite restrained. Mary’s story (and that of Jenny Trelawney, her fictional counterpart in Fled) contains so many twists and coincidences (lucky and unlucky), so many poignant and painful moments, that any writer who made it up out of whole cloth would be accused of melodrama. Her tale reads like fiction.

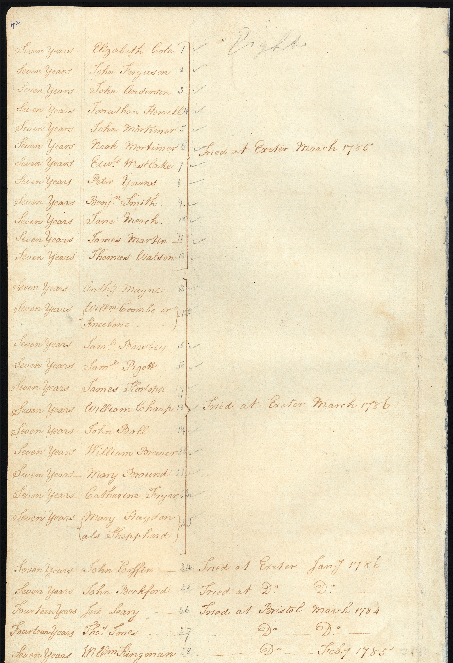

Mary Bryant, Convict indent Image credit: NSW State Archives and Records, accessed by ACT Historic Places, 18/05/2020

A female highway robber, living in the forest and bailing people up while dressed in breeches, sent for her crime to the other side of the world. An almost impossible voyage in a small, stolen open boat, over three thousand miles, with the last 700 or so in uncharted waters, gripping onto two young children while facing monstrous seas and the constant threat of capsize, starvation and death from thirst. Salvation, betrayal, recapture, and eventually a possible affair with one of the most famous men of the age, James Boswell.

One of the focal points of Mary’s tale, and of the novel, is of course the escape itself. But so many stars needed to align for it to happen at all. Mary and the other escapees needed knowledge of the local conditions, tides and currents. This they got from Aboriginals with whom they were friendly, with Mary’s husband Will taking indigenous families out to fish in government boats.

They needed a destination, and a means of navigating there. Fortunately for them, Governor Arthur Phillip had a blazing row with a visiting Dutch sea captain, Detmer Smit. The Bryants befriended Smit, and eventually learned from him of the Dutch colony of Coepang (Kupang, West Timor). Crucially, he also gave them a quadrant and a chart. If he had not visited Sydney Cove, or if he had been on better terms with Phillip, the convicts would have had nowhere to go. And they needed darkness. They got this on the night of March 28, 1791 – a new moon. That day, Detmer Smit’s ship had left, and the last remaining English ship had recently been sent to Batavia for provisions. Suddenly, there was no ship capable of pursuing them, just when the sky was at its blackest.

But while the details of Mary’s story are fascinating, the main reason she refused to leave me alone until I wrote about her was her character – her resourcefulness, her courage, and her refusal to be cowed. Since childhood, I’ve been captivated by the tale of a woman (and a convict at that) who navigated her way through a male-dominated world, and dragged her children to safety (at least for a while) across an angry sea.

Elizabeth Morton, Maid of all work

Similar to the records of Bryant, we know very little about Elizabeth Morton (b. 1804 - ?) – indeed she is barely a silhouette in the historical records. At present, Morton is the only known Ticket of Leave convict woman to have worked Lanyon Homestead around 1840 – located along one side of the Murrumbidgee that at the time was referred to as the ‘edge of legal occupation’. And although we know relatively little about Morton herself, at this site we have the luxury of timber slab, stone and brick huts, a kitchen, a barn and horse stables that date from the period when she worked here. These are the places where we can be sure, as a ‘housemaid of all work’ and possibly a dairy maid, Morton would have spent her days. Perhaps it was the more established phase in the history of Colony that lead to Morton’s less dramatic, but perhaps no less courageous life than Bryant’s? Below we contrast what we know of Morton’s life to that of Bryant - just two of our convict women among so many others.

The Magistrate’s records at the nearby town of Queanbyean indicate convicts and workers like Morton began their day on the property when a bell was rung - variously the records tell of convicts not responding to the bell to go to work, etc, and as can be seen in these images, to this day the c.1840 Kitchen retains a large bronze bell.

c.1840 Kitchen, Lanyon Homestead Image credit: ACT Historic Places, Lanyon Homestead Digital Guide

Bell at Lanyon Homestead, 2020 Image credit: Kate Gardiner

Like Mary Bryant, we haven’t found any records written by Elizabeth Morton herself. However, we can glean an idea of her physical appearance and her experience of being transported to the Colony of NSW based on historical records. Morton’s date of trial was 15 June 1835, in the London Central Criminal Court. At age 32, with no previous convictions and married with no children, she was charged with ‘robbery from a man’ and sentenced 7 years. Her place of origin was listed as Middlesex, London, it is noted she was literate, of Protestant faith, and that her occupation was ‘housemaid of all work’. These are the scant details we have of a woman, like Mary Bryant, who made up the estimated 164,000 women transported to the Colony of NSW.

As we have assembled the few known facts and dates for Morton, questions soon arise. What became of her husband in England? And what of her ocean voyage to the other side of the world? Without first-hand records by Morton, we are fortunate to have an account of the ship on which she was transported, the Henry Wellesley, through in the medical journal of Surgeon Superintendant Robert Wylie, dated from 27th August 1835 until the 20th February 1836[1];

‘The prisoners in the Henry Wellesley were generally healthy and the passage of four months an average one. The weather was favourable with two exceptions - an adverse gale in the channel and when in the limits of the north east trade, we had variable light winds, calms and heavy rain; at this juncture a great many of the prisoner's complained of severe head aches which were relieved by bleeding and purgatives. Two of the cases of fever which died, I think may be attributed to mental despondency and the seeds were probably latent in the system before they came on board, the third was a woman whose constitution was broken down by drinking ardent spirits. The two cases of cholera had nothing of the asphyxia, collapse or blue cholera in them, but the spasms were severe. I think there were some symptoms of scurvy in a few instances but they disappeared again and with the exception of the case of diarrhoea that was sent to the hospital, they were all landed in good health.

Surgeon Wylie makes reference to specific convicts in his subsequent notes, but not to Morton. But despite her absence in his notes, Wylie’s account suggests a journey of inclement weather bookended by 118 prisoners who were healthy at both the start and end of the voyage - a convenient comment for his professional reputation!

We might wonder how Morton’s 4-foot, 11 and-a-half-inch frame faired after the four-month journey across the oceans. And what was her mental state? As she stepped ashore did she, like Keneally’s character Jenny, momentarily grieve her faraway husband, friends and relatives? These are questions we can ponder about Morton alongside the carefully researched, fictionalised description of Jenny Trelawney’s voyage, and of the desperate conditions aboard ship interpreted in Keneally’s moving novel. Keneally’s novel is simultaneously a superb and sad imagining of the experience of transportation by hulk carrying both men and women. In light of that story, we can take some solace in that by the time she was transported in 1835, Morton had the relative luxury of traveling on a ship among only convict women. This is in comparison to Mary Bryant, transported almost 50 years earlier and who sailed in 1787 on the Charlotte, which held both male and female convicts.

Lanyon Homestead – c.1840 precinct outbuildings

Although we have no diary records for Elizabeth Morton, we can however gain a picture of her working life in the Colony of New South Wales because like the Kitchen building illustrated above, at Lanyon Homestead a number of other buildings likely to have been in existence during her time are still maintained as a part of this multi-layered heritage site. Views to nearby Mt Tennant and the Brindabella Range also remain the same – seen as a route of escape by some convicts, but promoted today as a majestic backdrop to the museum’s Barracks Café. Morton was likely residing at Lanyon by 1841, becuase a document registering a baptism for her three-month-old daughter (also named Elizabeth) took place on Sunday 19 September of that same year, and that document states the child’s parents’ abode is Lanyon, Parish of Queanbeyan, County Murray. This record indicates Morton was a dairy maid for the Wright family, and therefore that her days’ labour could have brought her to the hearth of the slab hut, or into the kitchen of the more substantial stone and brick building just up the hill.

Fireplace, c. 1835 Slab Hut, Lanyon Homestead Image credit: ACT Historic Places Digital Guide, Lanyon Homestead

Fireplace, c.1840 Kitchen (with c.1859 display items), Lanyon Homestead Image credit: ACT Historic Places Digital Guide, Lanyon Homestead

Seven years after her trial in London, Morton gains her Certificate of Freedom on Monday 22 May 1843. The general remarks on this precious document describe her features as follows; Lost a front upper tooth another inclining inwards. Three scrofula marks under right jaw and chin. Small wart on upper left eyelid. Nasal utterance. Marks of a burn back of right hand. These observations are the same as those listed for her in the ship's records when she arrived on the Henry Wellesley on 7 February 1836.

Convict-era costumes

In addition to heritage buildings, another way we can gain an understanding of daily life for any period in history is through clothing - from the cut and type of fabric, to the number of layers worn when we consider both the climatic conditions and daily activities the wearer was likely to have undertaken.

Fabric for convict costumes displayed at Lanyon Homestead was sourced by Jennifer Elton, Collections Manager at ACT Historic Places, and the garments were sewn by a talented volunteer. The fabrics used include a range of cottons, duck, muslins and wool blends. The female costume garments include a skirt, chemise, waistcoat, neck scarf, shawl, apron and bonnet. The garments representing male convicts include shirts and trousers[2]. Altogether, over 20 items were made so as to allow for rotation of individual costume items to keep them cared for over the duration of a permanent exhibition The Convict Years.

Female convict costume, 2020, ACT Historic Places display items Image credit: Jennifer Elton

The garments for the female costume were made using commercial dress patterns in size 14, and are machine sewn using standard dress making practices. There are no records describing exactly what was worn by the convicts who lived and worked at Lanyon, but we hope that our broad research and completed costumes provide a catalyst for discussion about life on the property during the convict era, c. 1835 - 1842.

Records from the period do however tell us that James Wright and John Lanyon, the landowners at the time, were required to clothe, house and provide food rations to their convict workers. Furthermore, there are historical records available from the Female Factories of the time that list the clothes that were to be supplied to women. It’s unclear if, as a Ticket of Leave convict, Morton was provided clothes by Wright, or if she would have continued to wear garments issued to her when she had arrived in the Colony five years earlier in 1836. We can only hope the layers she wore protected her against the cold winters below the Brindabella Range.

Male convict costume garments [detail], 2013, ACT Historic Places display items Image credit: Jennifer Elton

The shirt costume represents what convict men might have worn at Lanyon around 1840. This pattern was taken from an original convict shirt found in Hyde Park Barracks. The tough blue and white cotton mattress ticking fabric used in the construction of the shirt was full of even tougher slubs (a lump or thick place in the weave) which made hand sewing challenging and had the tendency to bend sewing needles! The exhibition shirt does not carry any of the issue markings as did convict clothing of the time. The Hyde Park Barracks shirt shows markings from where buttons would have been sewn to the collar.

In light of our speculations on the fabric and style of clothing likely to have been worn by a woman labouring at Lanyon, it is interesting to look at contemporary clothing worn in the district at the time. We are fortunate there is a photograph of Mrs Elizabeth McKenzie, wife of Alexander McKenzie (Ticket-of-Leave/Freedom convict and valued farmhand to James Wright).

Mrs Alexander McKenzie

For her portrait, Mrs McKenzie’s attire would likely have been her most valued garments (if in fact she owned them), including lace, ribbon and perhaps even a tartan weave, and they are more elaborate than what we can assume was worn by Morton. Given that McKenzie was a trained nurse and a highly regarded midwife, her attire alludes to her employment and assumed earnings working in such a vital role in the Limestone Plains community. And yet, looking at the fireplace, where the McKenzies lived in accommodation that was provided for them by Wright, it’s difficult to envisage her wearing this elaborate outfit day-to-day!

Fireplace, c.1840 Stable block (with c.1859 display items), Lanyon Homestead Image credit: Kate Gardiner

We hope you have enjoyed these glimpses of the heritage precinct, our conptemplations about Elizabeth Morton, and the insight to the extraordinary events of the life of Mary Bryant through Meg Keneally’s research.

To hear more from Meg Keneally about her experience writing the novel Fled, visit the Booktopia podcast here.

Take a virtual visit of Lanyon Homestead at the Google Cultural Institute here.

Engage in an interactive tour of Lanyon Homestead by downloading our Digital Guide here.

Lanyon Homestead is open Wednesday to Sunday, 10.00am – 4.00pm. Please check the website for changes to these hours; http://www.historicplaces.com.au/lanyon-homestead

[1]https://www.jenwilletts.com/convict_ship_henry_wellesley_1836.htm Accessed by ACT Historic Places on 18/05/2020

[2] Ward, L. 1998. Bicentennial dress pattern (kit). Powerhouse Museum, Sydney

Hero image: Silhouette portrait

Image source: The convict years exhibition, Lanyon Homestead